Editor’s note: The author gives examples of women characters from various Indian literary creations which continue to show women the path to truly becoming strong and powerful making their choices.

This essay was first published in a volume titled “Matter’s Logic and Spirit’s Dreams: A Sheaf of Essays” published by Center for Policy Studies, Visakhapatnam (2016). It is adapted from a Keynote Address delivered by the author at the Conference/Performance Conclave on ‘Epic Women’ held by Kartik Fine Arts in association with Arangham Trust on December 20-23, 2012 at Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Chennai. It is republished here with the kind permission of the publisher.

India alone has epic heroines who continue to live amongst us, directing our lives in a million ways. I grew up in Andhra Pradesh in my formative years. During the 1950s and 1960s, there were a series of brilliant evocations of epic heroines on the silver screen in Telugu. There was an unspoken law which kept the producers away from desiccating or glamorizing the heroines in these films. The women came to us as in Vyasa, Jaimini or any of the classic Telugu authors like Tirupati Venkata Kavulu.

The portrayals drew us closer to the classics in Sanskrit and Telugu. Somehow, somewhere, those black and white pictures were able to catch the imagination of the adolescent mind. One felt so very close to Draupadi in Narthanasala stinging Bhima to action. It was a kind of strengthening the girl’s backbone to face the future which was becoming a bigger and bigger question mark.

Another reason for our feeling close to the heroines was because in India the myths and legends of the past are not Dead Sea Scrolls. Sita, Savitri, Renuka, Draupadi and Kannaki are living heroines, role models in preparing, planning and executing our lives. Swami Vivekananda worked tirelessly for empowering Indian women and placed these role models before them:

“O India! forget not that the ideal of thy womanhood is Sita, Savitri, Damayanti. Sita is the name in India for everything that is good, pure, and holy, everything that in women we call woman.”

The Savitri vrata is observed as Karadaiyan nonbu by the Tamilians, Vat-Savitri by the Maharashtrians and so on. Renuka not only reigns over the Padaiveedu temple but is found in thousands of temples as Mariamman or Ellamma or Pydamma. I need not remind the audience of Draupadi Amman festivals in India, one of which inspired the great Tamil poet Subramania Bharati to write his magnificent epyllion, Panchali Sapatham. Kannaki who was iconised in Silappadhikaram itself is worshipped in South India and Sri Lanka.

Yes. The epic heroines and heroines in history faced such challenges with great determination. Mahatma Gandhi held such a view, as I see from his correspondence with my mother-in-law, Srimati Ranganayaki Thatham. Obviously she had problems in the family and had been advised

patience by Gandhi.

When she retorted angrily to his advice whether she should blind her eyes like Gandhari, he replied suavely and to the point that Ranganayaki should not accept literally all that is written in the Mahabharata. Gandhari could have served her husband better if she had kept her eyes open. The self-binding of her eyes must be taken as a symbol and no more. “Do not bind your eyes literally or metaphorically. Use them and serve your husband well. Serving one’s husband is not blind adoration. When her husbands were helpless, did not Draupadi speak angrily to

them?”

***

Coming back to the subject, we find that caste has never favoured the talented woman. Yet there is the 16th century Telugu poetess Molla whom Nabaneeta Dev Sen admires no end. Molla was doubly tainted, being a Sudra, says Dr. Nabaneeta:

“Although Molla is very popular today, she was silenced in her time, her Ramayana barred from the King’s court. The potter’s daughter, turned classical poet, was rejected because of her caste and gender. Literary excellence was not enough to win recognition in the court.”

However, it must be admitted that caste and gender have never been too oppressive for people who joined the stream of Bhakti Movement. When the Western influence and English education allowed new breeze to blow across our land, a transformation in creative writing began in a big way. People went back to epic heroes and heroines as well as historical personalities. Sri Aurobindo finds this a great help for the creative artist who is interested in conveying a message to the audience.

“If the plot is new,

~ CWSA, Vol. 4, p. 789

The mind is like a traveller pressed for time,

And quite engrossed with incident, omits

To take the breath of flowers and lingering shade

From haste to reach a goal. But the plot old

Leaves it [the mind] at leisure and it culls at ease

Those delicate, scarcely-heeded strokes, which art

Throws in, to justify genius. These being lost

Perfection’s disappointed. Then if old

The subject amplifies creative labour,

For what’s creation but to make old things

Admirably new; the other’s mere invention,

A small gift, though a gracious. He’s creator

Who greatly handles great material,”

“He’s creator / Who greatly handles great material.” India’s classical myths and legends provide great material.

Sita is one such great material. We have such a great creator in the Malayalam poet Kumaran Asan who wrote Chintavishtayaya Sita in 1919. According to Sukumar Azhikode, Sita is seen here as “a critical, sharp-tongued, passionate woman speaking out for the legitimate rights of the women of all times”, and yet she calms down remembering her father’s ways described by Valmiki, for she is full of sorrow and the glow of the Eternal Feminine. She tells herself that even towards someone who has treated her so unfairly, she should not have hatred:

“My thoughts are carried back

To the selfsame love you so tenderly

Bore in your heart for all creation,

Tree or bird or beast, the same affection you

Had for men and gods alike.”

The conclusion in Kumaran Asan’s reading of Sita is so natural, not quite unexpected but has a terrible beauty about it all the same. After the entire narrative based in the sylvan surroundings of Valmiki’s hermitage where Sita had sat in reverie comes to a conclusion, we enter the Court of Ayodhya for those few, last lines:

“Her comely head bent and eyes fastened on

The feet of the Sage conducting his precious

Charge to her husband’s court,

Sita followed Him where the great nobles waited upon

The king. She spoke no word. She gave one look

At her husband’s anguished face. A glance

At the assembled court. The next moment

She had released herself and stepped across

The great divide.”

This is how myths are transformed to gain entry into contemporary hearts. No coming of Vasundhara from the depths of the earth seated on a throne. Chintavishtayaya Sita was a great favorite of my father, Prof. K.R. Srinivasa Iyengar. He knew no Malayalam, but he used to read with

wet eyes Bhaskaran’s translation, and the poem inspired father to insert an extended, powerful soliloquy of Sita in his English epic Sitayana, bring her further down to our own times making her cogitate on issues like the Nuclear Horror.

***

Looking back on our classical myths and legends, it is wonderful to note how writers have been re-formatting these works to help woman fight back. Draupadi is brought to the Pandava court and held out as the property of the Kauravas. Is woman no more than a chattel that can be bought and sold, that can be won or lost in a game of dice? When appealed to by Draupadi, Bhishma is helpless and talks of the sanctions of Dharma in this version by the renowned poet Subramania Bharati:

“Dharma sanctions

Your sale as a slave.

I know what they do here

Is repugnant beyond measure.

But Sastras and customs

Are alike against you.

Impotent am I to halt this evil.”

Draupadi answers:

“Finely, bravely spoken Sir!

When treacherous Ravana, having carried away

And lodged Sita in his garden,

Called his ministers and law-givers

And told them the deed he had done,

These same wise old advisers declared:

Thou hast done the proper thing:

Twill square with dharma’s claims!

When the demon king rules the land

Needs must the sastras feed on filth!…”

I could go on in this fashion. There is S.K. Ramarajan’s Tamil epyllion Meghanadam (1956) which has Indrajit’s Sulochanai as the heroine. How helpless a woman can be, when she speaks out for Dharma! Indrajit has no answers for Sulochanai’s questions. Like Bharati’s Draupadi who wonders whether the land has no man to come forward to stand up for Dharma when an innocent woman is dragged and disrobed in a royal court, like Kannaki who cries out whether Madurai city has not a single man to speak out against the wrong done to her by executing her innocent husband, like Sita who exclaims whether Lanka has no man to give wholesome advice to Ravana, Sulochanai tells Indrajit:

“My handsome Lord! When your father

Imprisoned the beautiful Sita,

Were there no wise men here

To warn him: The eyes of chaste women?

They are balls of fire; their cloud-like

Tresses? They are Yama’s noose

Terrible. Their body is a tender creeper?

No, they are powerful lightning!”

Are there other ways of reading the epic heroines apart from such somber retellings? Can we inject humour to trace the truths in the lives of the past?

This way of rereading the epic characters could be in the style of my mother-in-law, the renowned Tamil writer, Ranganayaki Thatham, also known as Kumudini. Her long life was one of deep involvement with the plight of women. The Gandhian institution, Tiruchi Seva Sangam that she founded in 1948 has given a new life to thousands of orphaned and abandoned girl children and women.

Though involved in such serious social work, she felt that woman brought on much of her problems by not protesting at the right time. In her brilliant drama, Viswamitrar she imagines a situation when Chandramati refuses to go in exile with Harischandra. A pointed introduction tells us of the thought-movements of Kumudini in the matter of women’s independence:

“It is usual to say that one cannot triumph over destiny. Yet, some with their ability and cleverness, are able to control even destiny.

“In the original story when Harishchandra left the country, Chandramati went along with him without any qualms and endured privation along with him. Savitri, on the other hand, learnt in advance about the departure of Satyavan from this earth and as soon as that time came, made appropriate arrangements and followed Yama who is not visible to human eyes, defeated him and got her husband back, and in the process, earned two boons as well.

“If, in Chandramati’s place, there had been a woman like Savitri, what would have been the fate of Viswamitra?”

One has to read the play to understand the various nuances of female power. If only woman would use it with due circumspection, while anchoring herself firmly in the family, what can even a fiery ascetic do?

Caught in the mazes of the nation’s politics, bedeviled by the foreign minister’s statesmanship to marry the twenty seven daughters of Anga’s king, the return of his companion Menaka demanding a place by his side in the throne, Viswamitra can do nothing but run away. And that is exactly what he does!

I have enjoyed this play of Kumudini since I was ten years old and have drawn the needed lessons from it. Her other play, Varied Advice is also a reinterpretation of epic heroines in the light of contemporary culture. This play was actually produced as a musical. She flayed the patriarchal system which gave the choice to man.

Despite their heroism and virtue, would a girl choose any of the ancient heroes as her life’s partner? But then, did the contemporary girl have any choice? Often her parents were full of self-pity so she preferred not to burden them more and accepted what came by her way; or they were in search of a fat catch in the marriage market, a Suitable Boy.

The young Gita has no idea how to choose from the list presented by her enlightened family. IAS, CA, an engineer in Dubai or Doha minting gold or the son of a cabinet minister? After a whole scene of rib-ticklers, all go away and Gita falls asleep.

Now come several epic heroines to her in her dream. First is Sita. Gita’s question evokes a speedy answer. She can choose anyone but not someone who professes lofty ideals. Draupadi comes. Her hair is still unplaited. Hasn’t Dushasana been killed and his blood pasted on her tresses, asks Gita. Draupadi’s answer is typical of Kumudini’s humour in this play and elsewhere.

“A matter of habit, child. I have become used to wandering around with my hair loose. Besides this is now the fashion. I just cannot gather my tresses.”

When Gita asks for advice, Draupadi has no hesitation in answering her:

“You can marry the hunter who wanders in the forests;

Or a highway robber; or a horrible fellow

Who might beat you black and blue; Even a fifty year old doddery chap.

But never, never a man who is a gambler.”

Damayanti appears and assures Gita that one who runs away from the responsibilities of the house should be studiously avoided. Chandramati is all thunder and lightning. No, Gita should never opt for someone who insists upon telling the truth. It is now the turn of Sakuntala to sail into the vision and warn the sleeping girl against marrying one whose memory is weak. What kind of domesticity is possible with such a person?

“Did you post the letter? I forgot.

Where is the tomato? I don’t remember.

What about coffee powder? Ah, my memory

Slipped and so I did not buy…

So I did not give you housekeeping money?

Where did I leave my box?

Who is my wife? I don’t remember!

Gita, beware a person with weak memory!”

There is then Radha who says one should learn to identify the mood of the husband to keep him under control at all times. Surely not an easy task!

The last to come is Savitri who advises Gita not to worry but just look after the husband, whoever he be, as her eleventh child. According to her, the whole problem arises because we think of men as heroic, a helpmate, a guardian, a provider and so on. Naturally there is disappointment. Why have high expectations about men? Certainly they are no repositories of all the glory we praise day in and day out. We have to make do with them! They are just babies, no more! So use the Vedic blessing: dasaasyaam putraanaam patim ekaadasam kuru!

When Gita wakes up she is delighted that her problem has been solved in a trice. Gita, her mother, aunt and grandmother now sing in unison, dancing on the stage:

“Problem has been solved! Yes!

Husbands are just children,

The last baby for the wife.

In outside world they are heroes,

Within home, just prattling babes.

B.A., C.A., M.A., M.D.,

B.E., P.P., but a child.

Musician, scholar, Vice chancellor

At home they are weeny babes.

Pilot, Scientist also babes only.

M.P., M.L.A., they are babes too,

Minister, sinister, all be kids.

Problem has been solved!

Yes, indeed!”

Very rarely staged, yet, Varied Advice (Buddhimatigal Palavitam), has never failed to tickle the audience to a wiser view of life.

There have also been other ways of looking at our epic heroines. Remember, their lives have not been in vain. We would do well to conclude with Savitri whose story of paaativratya (vowed to her husband) I am afraid has not been rightly understood in a male-dominated society that has sought to trap female chastity with iron chains.

Savitri’s story is not regressive at all. If we get back to the original Upakhyana in the Mahabharata, we would see her as very brave, very free, very loving and very duty-conscious, the ideal woman who can uplift a whole race. Unfortunately the twists and turns of Katha-telling has made her into one who played a cheap trick on Yama by asking for one hundred children. He granted her request and then, says the modern narrator, Yama realised the faux pas and had to release Satyavan’s life, lest the ideal of female chastity get tarnished.

On the contrary, in Vyasa’s narrative, Savitri emerges as a strong lady who first empowered herself before facing the crisis. Vyasa tells us that three days prior to the day foretold by Rishi Narad, Savitri undertook the rigorous Three-nights Vow, Tri-rattra Vrata. She fasted, meditated day and night and stood still appearing like a block of wood (kaashtabhuteva). On the concluding day she performed a fire-sacrifice. Now what does the Tri-rattra vrata signify?

The Vedas have two major divisions: Purva Mimamsa (Rituals) & Uttara Mimamsa (Philosophy). According to the path of Purva Mimamsa, it is not merely faith in one receiving the fruits of the rituals. We are told that a power descends into the person performing it and remains with him till the fruits are realized.

“The Mimamsakas have attempted to answer the question how a remote result, say, the attainment of heaven, is obtained by an action such as a sacrifice, which belongs to and in fact ceases in the present. Injunctive texts ordain that the fruits, namely, heaven and the like, should be achieved by sacrifices such as darsa-paurnamasa. And this implies that the sacrifice is means to the fruit, viz., Heaven.

“A sacrifice is the nature of an action which is very soon lost. Hence the instrumentality of the sacrifice to the fruit which is to take place at a distant time is hardly possible. To establish this instrumentality, which is propounded by the Sruti, between sacrifice and heaven, an invisible potency is admitted which issues from the sacrifice and which endures till the fruit is generated and which resides in the soul of the sacrificer. This is called apurva. It ceases on producing the result…It is a power in the sacrifice.”

No doubt Savitri’s aim had been non-widowhood (avaidhavya). She needed a power to help her achieve it and the Vedic ritualism gave her such a power. There is no other explanation for Savitri’s ability to follow Yama beyond the earth when the dire god was taking away Satyavan’s “thumb-sized life”. This is mentioned clearly by Vyasa. Niyamavrata samsiddhaa mahabhaagaa pativrataa.

Read more by the author HERE.

Sita is an epic heroine who dares to question Rama with satiric barbs when he points out that as a woman she would find it difficult to live in the forest. Of course Sita did it in privacy and with a sense of loving possession: pranayaascha abhimaanaancha parichikshepa raghavam. She asks him questions. What is this about her being termed weak and from whence this fear in Rama to take her to the forest? After living with her all these years, hasn’t he realised her strength of mind? Isn’t she like Savitri, the brave wife of Dyumathsena’s son, Satyavan: Satyavantha manuvrataam savitrimiva maam vidhdhi?

In the end, Rama gives in for he really loves her no end. And then says something which I have always wondered whether Rama was not testing the woman in Sita, after all. What do we hear today all the time when men chat? Or exchange emails? Ah, women are possessive of material things, they love luxury, jewels, sarees, scents… Anyway Valmiki’s Rama tells her that prior to going, she will have to give away quickly all her possessions.

Apparently Rama does not know the in-depth psyche of women. Sita smiled immediately, says Valmiki. Kshipram pramudita devi! Was it due to happiness at her having won the day or was there a trace of derision at the way a man’s mind moves? All that we know is that Sita is ready to sacrifice the frills of everyday living at a moment’s notice, and with a smile.

Salute to this smiling manasvini, Sita!

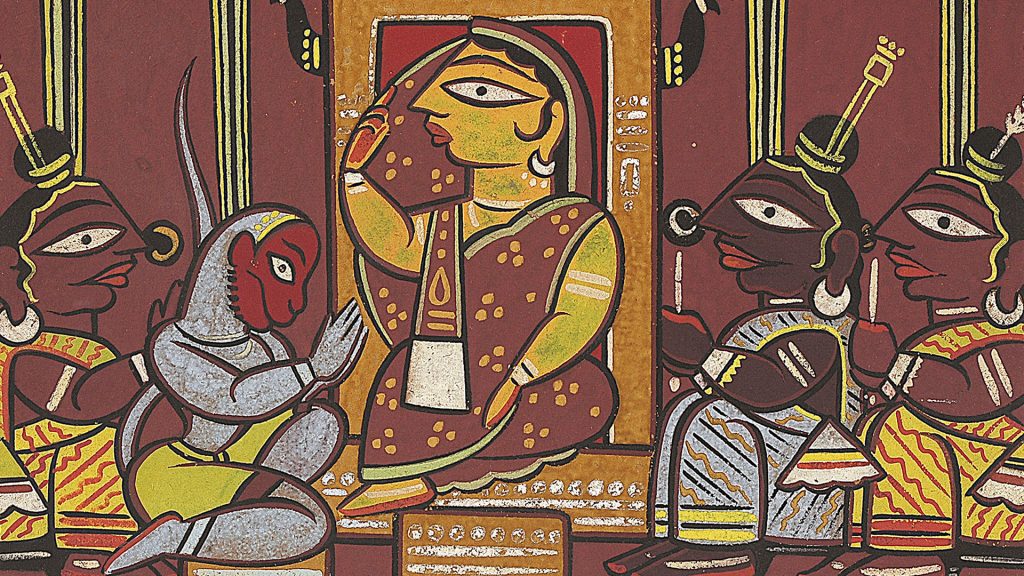

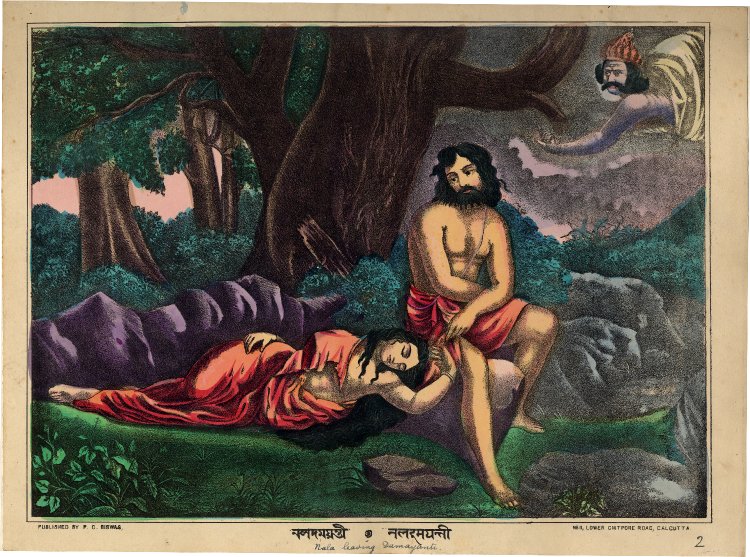

Cover image:

The humiliation of Draupadi, Kangra painting, circa 1830-1840

(source)