Humility is that state of consciousness in which, whatever the realisation, you know the infinite is still in front of you. . . you need to be humble not only when you have nothing substantial or divine in you but even when you are on the path of transformation.

The Mother, CWM, Vol. 3, p. 175

The Only True Humility

To be humble means for the mind, the vital and the body never to forget that without the Divine they know nothing, are nothing and can do nothing; without the Divine they are nothing but ignorance, chaos and impotence. The Divine alone is Truth, Life, Power, Love, Felicity.

Therefore the mind, the vital, and the body must learn and feel, once and for all, that they are wholly incapable of understanding and judging the Divine, not only in his essence but also in his action and manifestation.

This is the only true humility and with it come quiet and peace.

This is also the surest shield against all hostile attack. Indeed, in the human being it is always the door of pride at which the Adversary knocks, for it is this door which opens to let him enter.

(The Mother, CWM, Vol. 14, pp. 152-153)

Humility, a perfect humility, is the condition for all realization. The mind is so cocksure. It thinks it knows everything, understands everything. And if ever it acts through idealism to serve a cause that appears noble to it, it becomes even more arrogant more intransigent, and it is almost impossible to make it see that there might be something still higher beyond its noble conceptions and its great altruistic or other ideals. Humility is the only remedy.

I am not speaking of humility as conceived by certain religions, with this God that belittles his creatures and only likes to see them down on their knees. When I was a child, this kind of humility revolted me, and I refused to believe in a God that wants to belittle his creatures. I don’t mean that kind of humility, but rather the recognition that one does not know, that one knows nothing, and that there may be something beyond what presently appears to us as the truest, the most noble or disinterested.

True humility consists in constantly referring oneself to the Lord, in placing all before Him. When I receive a blow (and there are quite a few of them in my sadhana), my immediate, spontaneous reaction, like a spring, is to throw myself before Him and to say, ‘Thou, Lord.’ Without this humility, I would never have been able to realize anything. And I say ‘I’ only to make myself understood, but in fact ‘I’ means the Lord through this body, his instrument. When you begin living THIS kind of humility, it means you are drawing nearer to the realization. It is the condition, the starting point.

(The Mother, Agenda, Vol. 1, pp. 125-126)

What is the right and the wrong way of being humble?

It is very simple, when people are told “be humble”, they think immediately of “being humble before other men” and that humility is wrong. True humility is humility before the Divine, that is, a precise, exact, living sense that one is nothing, one can do nothing, understand nothing without the Divine, that even if one is exceptionally intelligent and capable, this is nothing in comparison with the divine Consciousness, and this sense one must always keep, because then one always has the true attitude of receptivity—a humble receptivity that does not put personal pretensions in opposition to the Divine.

(The Mother, CWM, Vol. 5, p. 45)

There is one thing that has always been said, but always misunderstood, it is the necessity of humility. It is taken in the wrong way, wrongly understood and wrongly used. Be humble, if you can be so in the right way; above all, do not be so in the wrong way, for that leads you nowhere. But there is one thing: if you can pull out from your-self this weed called vanity, then indeed you will have done something. But if you knew how difficult it is!

You cannot do a thing well, cannot have a fine idea, cannot have a right movement, cannot make a little progress without getting puffed up inside (even without being aware of it), with a self-satisfaction full of vanity. And you are obliged then to hammer it hard to break it. And still broken bits remain and these begin to germinate.

One must work the whole of one’s life and never forget to work in order to uproot this weed that springs up again and again and again so insidiously that you believe it is gone and you feel very modest and say: “It is not I who have done it, I feel it is the Divine, I am nothing if He is not there”, and then the next minute, you are so satisfied with yourself simply for having thought that!

(The Mother, CWM, Vol. 5, pp. 44-45)

Spiritual Humility Within

A spiritual humility within is very necessary, but I do not think an outward one is very advisable (absence of pride or arrogance or vanity is indispensable of course in one’s outer dealings with others)—it often creates pride, becomes formal or becomes in effective after a time. I have seen people doing it to cure their pride, but I have not found it producing a lasting result.

***

It [to feel like doing namaskar to everyone] is a feeling which some have who either want to cultivate humility (X used to do it, but I never saw that it got rid of his innate self-esteem) or who have or are trying to have the realisation of Narayan in all with a Vaishnava turn in it. To feel the One in all is right, but to bow down to the individual who lives still in his ego is good neither for him nor for the one who does it. Especially in this Yoga it tends to diffuse what should be concentrated and turned towards a higher realisation than that of the cosmic feeling which is only a step on the way.

***

It is only this habit of the nature—self-worrying and harping on the sense of deficiency—that prevents you from being quiet. If you threw that out, it would be easy to be quiet. Humility is needful, but constant self-depreciation does not help; excessive self-esteem and self-depreciation are both wrong attitudes. To recognise any defects without exaggerating them is useful but, once recognised, it is no good dwelling on them always; you must have the confidence that the Divine Force can change everything and you must let the Force work.

(Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 28, p. 429)

***

But that [inability to recognise one’s defects] is a very common human weakness, although it ought not to exist in a sadhak whose progress depends largely on his recognising what has to be changed in him. Not that the recognition by itself is sufficient, but it is a necessary element. It is of course a kind of pride or vanity which considers this necessary for strength and standing. Not only will they not recognise it before others but they hide their defects from themselves or even if obliged to look at it with one eye look away from it with the other. Or they weave a veil of words and excuses and justifications trying to make it something other than it really is.

(Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 31, pp. 241-242)

Superiority and Humility

As for the sense of superiority, that too is a little difficult to avoid when greater horizons open before the consciousness, unless one is already of a saintly and humble disposition. There are men like Nag Mahashoy in whom spiritual experience creates more and more humility, there are others like Vivekananda in whom it erects a giant sense of strength and superiority—European critics have taxed him with it rather severely; there are others in whom it fixes a sense of superiority to men and humility to the Divine. Each position has its value.

Take Vivekananda’s famous answer to the Madras Pundit who objected to one of his assertions, “But Shankara does not say so.” To which Vivekananda replied, “No, Shankara does not say so, but I, Vivekananda, say so”, and the Pundit sank back amazed and speechless. That “I, Vivekananda” stands up to the ordinary eye like a Himalaya of self-confident egoism.

But there was nothing false or unsound in Vivekananda’s spiritual experience. This was not mere egoism, but the sense of what he stood for and the attitude of the fighter who, as the representative of something very great, could not allow himself to be put down or belittled.

This is not to deny the necessity of non-egoism and of spiritual humility, but to show that the question is not so easy as it appears at first sight. For if I have to express my spiritual experiences, I must do it with truth—I must record them, their bhāva, the thoughts, feelings, extensions of consciousness which accompany them.

What can I do with the experience in which one feels the whole world in oneself or the force of the Divine flowing in one’s being and nature or the certitude of one’s faith against all doubts and doubters or one’s oneness with the Divine or the smallness of human thought and life compared with this greater knowledge and existence? And I have to use the word “I”—I cannot take refuge in saying “this body” or “this appearance”,—especially as I am not a Mayavadin. Shall I not inevitably fall into expressions which will make X shake his head at my assertions as full of pride and ego? I imagine it would be difficult to avoid it.

(Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 32, p. 113)

Self-Respect, Amour-Propre, Superiority

Self-respect and a sense of superiority are two very different things. Self-respect is not necessarily a sign of egoism any more than its absence is a sign of liberation from egoism. Self-respect means observing a certain standard of conduct which is proper to the level of manhood to which I belong—e.g. I cannot make a false statement out of self-respect though it would be advantageous to do it and most people under the circumstances would make it. Amour-propre is different and belongs to the sattwic type of ego. When one is not free from ego, then amour-propre (as well as self-respect—for that can be with ego or without ego) is a necessary support for the maintenance of the personality at its proper level.

***

Amour-propre does not mean conceit. It means at its best the feeling not to make mistakes and to do as well as possible—at its worst it means to try to appear well and without mistakes or faults to others and not to like faults being pointed out.

***

Ideas of superiority and inferiority are not of much use or validity. Each one is himself with his own possibilities to which there need be no limit except that of will and development and time. Each nature has its own lines and own things that are more developed or less developed, but the standard should be set by what he in himself aims to be. Comparison with others brings in a wrong standard of values.

(Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 31, pp. 243-244)

Don’t miss:

Egoism and Its Forms: Becoming Conscious with Guidance from Sri Aurobindo

By Oneself One is Nothing and Can Do Nothing

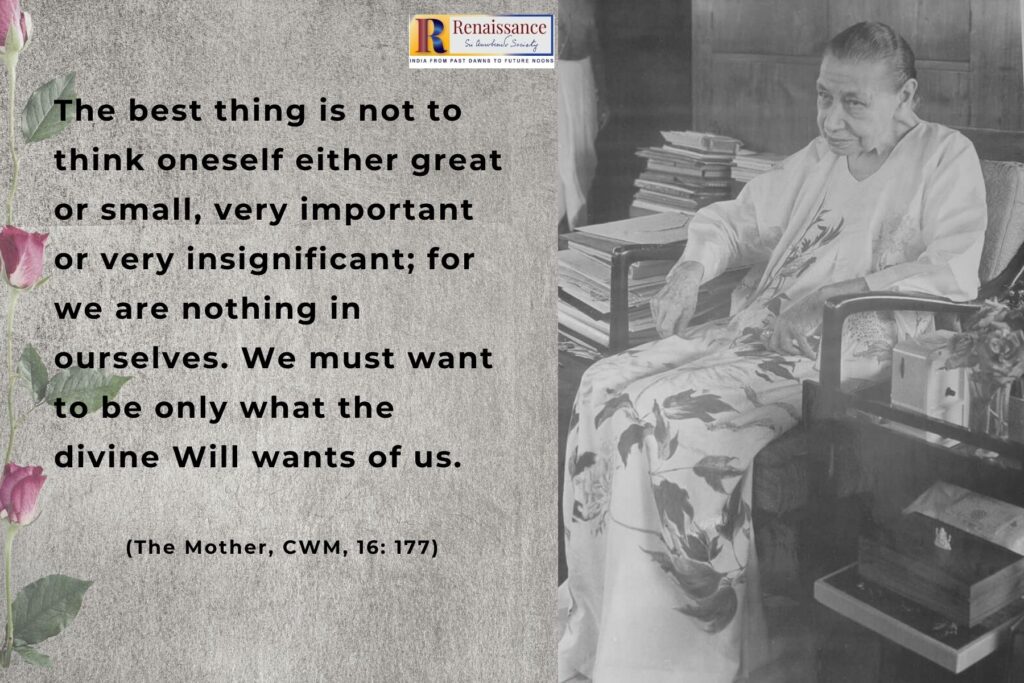

Disciple: All my good intentions, since my childhood, have been of no worth. My nature is just what it was when I was a child. I can scarcely hope that it will be transformed; and after all, is it worth the trouble to try and transform it? It is better not to think of this personal nature as mine; not to identify myself with it is the best remedy I can find against the lower and inconscient nature.

The Mother: Nothing of all this is the right attitude. So long as you oscillate between wanting to transform yourself and not wanting to transform yourself—making an effort to progress and becoming indifferent to all effort through fatigue—the true attitude will not be there. All your observations should lead you to one certainty, that by oneself one is nothing and can do nothing. Only the Divine is the life of our life, the consciousness of our consciousness, the Power and Capacity in us. It is to Him that we must entrust ourselves, give ourselves without reserve, and it is He who will make of us what He wants in His infinite wisdom.

(The Mother, CWM, Vol. 16, p. 177)

***

The egoism of the instrument can be as dangerous or more dangerous to spiritual progress than the egoism of the doer. The ego-sense is contrary to spiritual realisation, so how can any kind of ego be a thing to be encouraged? As for the magnified ego, it is one of the most perilous obstacles to release and perfection. There should be no big I, not even a small one.

What is meant by the magnified ego is that when the limits of the ordinary mind and vital are broken, one feels a far vaster and more powerful consciousness and unlimited possibilities, but if one ties all that to the tail of one’s own ego, then one becomes a thousand times more egoistic than the ordinary man. The greatness of the Divine becomes an excuse and a support for one’s own greatness and the big I swells itself to fill not only the earth but the heavens. That magnification of the ego is a thing to be guarded against with a watchful care.

(Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 31, p. 231)

The Examiners

The integral yoga consists of an uninterrupted series of examinations that one has to undergo without any previous warning, thus obliging you to be constantly on the alert and attentive.

Three groups of examiners set us these tests. They appear to have nothing to do with one another, and their methods are so different, sometimes even so apparently contradictory, that it seems as if they could not possibly be leading towards the same goal. Nevertheless, they complement one another, work towards the same end, and are all indispensable to the completeness of the result.

The three types of examination are: those set by the forces of Nature, those set by spiritual and divine forces, and those set by hostile forces. These last are the most deceptive in their appearance and to avoid being caught unawares and unprepared requires a state of constant watchfulness, sincerity and humility.

The most commonplace circumstances, the events of everyday life, the most apparently insignificant people and things all belong to one or other of these three kinds of examiners. In this vast and complex organisation of tests, those events that are generally considered the most important in life are the easiest examinations to undergo, because they find you ready and on your guard. It is easier to stumble over the little stones in your path, because they attract no attention.

Endurance and plasticity, cheerfulness and fearlessness are the qualities specially needed for the examinations of physical nature.

Aspiration, trust, idealism, enthusiasm and generous self-giving, for spiritual examinations.

Vigilance, sincerity and humility for the examinations from hostile forces.

And do not imagine that there are on the one hand people who undergo the examinations and on the other people who set them. Depending on the circumstances and the moment we are all both examiners and examinees, and it may even happen that one is at the same time both examiner and examinee. And the benefit one derives from this depends, both in quality and in quantity, on the intensity of one’s aspiration and the awakening of one’s consciousness.

To conclude, a final piece of advice: never set yourself up as an examiner. For while it is good to remember constantly that one may be undergoing a very important examination, it is extremely dangerous to imagine that one is responsible for setting examinations for others. That is the open door to the most ridiculous and harmful kinds of vanity. It is the Supreme Wisdom which decides these things, and not the ignorant human will.

(The Mother, CWM, Vol. 14, pp. 42-43)

***

Shocks and trials always come as a divine grace to show us the points in our being where we fall short and the movements in which we turn our back on our soul by listening to the clamour of our mental being and vital being.

If we know how to accept these spiritual blows with due humility, we are sure to cover a great distance at a single bound.

(The Mother, CWM, Vol. 14, p. 219)

~ Graphic design: Beloo Mehra