CONTINUED FROM PART 2

The Story of Ramayana

Sri Aurobindo admired Ramayana for its structure and simplicity of plan. He wrote:

The whole story is from beginning to end of one piece and there is no deviation from the stream of the narrative.

~ CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 349

It is the story of Rama’s banishment, Sita’s imprisonment and the destruction of Ravana. We follow the hero’s adventures step by step, — as he walks with Viswamitra in the Bala Kanda and later when he crosses the Ganges with Guha in the Ayodhya Kanda, or as he journeys in Dandaka with Sita and Lakshmana in the Aranya Kanda. We follow him when he meets Sugriva in the Kishkinda Kanda, when he listens to Sita’s message from Hanuman in the Sundara Kanda, and as he destroys Ravana in the Yuddha Kanda.

Several times ‘the tale so far’ is recapitulated. Repetitions are used as brush strokes to make the structure absolutely clear. Though the epic is long, nowhere do we miss the main thread of the story. And yet, the epic has several carefully-laid minute details that together form a wealth of unforgettable scenes involving a variety of characters.

* * *

In the opening cantos Valmiki is the hero. We see him before us as he listens intently to Narad’s description of Rama as the ideal man. And he is walking the banks of Tamasa, enjoying the scenic grandeur in the company of his student, Bharadhwaja. We see him struck by pain and a nameless anger as he watches the lament of the female krauncha mourning the sudden death of its mate.

There again he is, listening to Brahma who reassures the Rishi about his poetic capabilities. And we also see him sitting silently in yoga, as the entire Ramayana unveils before him as a cinematograph in the third Sarga of the Bala Kanda.

Passing with ease into the unplumbed depths

~ Bala Kanda, Sarga 3, Slokas 6-7, Translated by K. R. Srinivasa Iyengar, The Epic Beautiful (1983), p. 55.

Of yogic meditation,

He saw everything as a gooseberry

set on the palm of his hand.

Having seen all exactly as they once

happened, the Sage indited

the beauty and bounty of Rama’s life

in verse of compelling charm.”[2]

One is reminded of Sri Aurobindo himself sitting motionless in an upstairs room in Pondicherry as Savitri was in the making.

According to him neither was the philosophical content carefully planned nor were the mystic flights results of an unfettered imagination. Like Valmiki, he saw and wrote it down.

I have not anywhere in Savitri written anything for the sake of mere picturesqueness or merely to produce a rhetorical effect; what I am trying to do everywhere in the poem is to express exactly something seen, something felt or experienced; if, for instance, I indulge in the wealth-burdened line or passage, it is not merely for the pleasure of the indulgence, but because there is that burden, or at least what I conceive to be that, in the vision or the experience. . .

Savitri is the record of a seeing, of an experience which is not of the common kind and is often very far from what the general human mind sees and experiences.

~ CWSA, Vol. 27, p. 343

This was a lifetime’s conviction after having tried to record all that he saw when composing Savitri.

The pictures had formed of themselves from the depths of Sri Aurobindo’s yogic trances. That this could be so, that such yogic stillness could lead to the enriching digging of the depths of the infinite within oneself and come out with the vastnesses of its manifestation as the finite without, had perhaps been shown to him when he met Valmiki in the opening cantos of the Ramayana decades earlier at Baroda.

The Ramayana seemed to tell a story, but it was certainly no ordinary story.

It was not merely that of a Prince’s exile, the kidnapping of his wife and her rescue after killing the kidnapper-king in a battle. If it were so, the story could not have endured the pitiless judgment of time. Nor could it have caught the imagination of peoples all over Asia.

There surely were imbedded spiritual radiances within the tale which came from a yogic poet’s prophetic vision and it is these radiances that have made the story dear, purposeful and aesthetically appealing.

Sri Aurobindo went to the heart of the matter when he remarked thus in an unfinished article, ‘The Genius of Valmiki’ (later titled, ‘The Voices of the Poets’)

The kavi or vates, poet & seer, is not the manishi; he is not [the] logical thinker, scientific analyser or metaphysical reasoner; his knowledge is one not with his thought, but with his being; he has not arrived at it but has it in himself by virtue of his power to become one with all that is around him.

By some form of spiritual, vital and emotional oneness, he is what he sees; he is the hero thundering in the forefront of the battle, the mother weeping over her dead, the tree trembling violently in the storm, the flower warmly penetrated with the sunshine. And because he is these things, therefore he knows them; because he knows thus, spiritually & not rationally, he can write of them.

~ CWSA, Vol. 12, p. 405

Because of this spiritual-vital-emotional identification, the Ramayana becomes one vast gallery of memorable portraits, each a unique symbol of the ways of the world.

If Rama is seen as a figure of Dharma, Sita of chastity and Lakshmana of service (kainkarya), there are also others who exist as themselves within their confines, and yet are an invaluable part of the main story. Guha the boatman, Sabari the Ashram maid, Tara the Vanara queen, Trijatha the Rakshasa woman: Sarga after Sarga throws up such pearls of character, each worthy of taking the lead in an epic. Even the villains and base women provoke our thoughts, kindle our imagination and create the stirrings of compassion in our hearts. Kaikeyi, Kabandha, Lankini, Akshaya Kumara: prisoners of circumstance, all!

And every single character in the Ramayana makes us think of ourselves, our hopes and despairs, our aspirations and anxieties, our basenesses and perfidies, our attempts to break out of the egoistic hell-charms of pride and cupidity, our successes, failures and renewed endeavours to ascend the ladder of perfection with Rama and Sita in the lead.

Valmiki has not told the tale as a mere remembrance of things past. The Ramayana has been written not for passing one’s leisure-time as the battle-drums fall silent, and the soldiers rest in their tents over cups of wine after victory-celebrations.

The epic is a path-finder, a character-builder, a time-table document for attaining human perfection.

Sri Aurobindo recognised this while comparing Indian legends with Greek myths in his letter to Manmohan Ghose:

Inferior in warmth and colour and quick life and the savour of earth to the Greek, they had a superior spiritual loveliness and exaltation; not clothing the surface of the earth with imperishable beauty, they search deeper into the white-hot core of things and in their cyclic orbit of thought curve downward round the most hidden fountains of existence and upward over the highest, almost invisible arches of ideal possibility.

Let me touch the subject a little more precisely. The difference between the Greek and Hindu temperaments was that one was vital, the other supra-vital; the one physical, the other metaphysical; the one sentient of sunlight as its natural atmosphere and the bound of its joyous activity, the other regarding it as a golden veil which hid from it beautiful and wonderful things for which it panted. The Greek aimed at limit and finite perfection, because he felt vividly all our bounded existence; the Hindu mind, ranging into the infinite tended to the enormous and moved habitually in the sublime.

~ CWSA, Vol. 36, p. 128

But as Sri Aurobindo is quick to point out, “the infinite is not for all to meddle with; it submits only to the compulsion of the mighty” (ibid).

The story of Rama has been told hundreds of times, but Valmiki remains unsurpassed till today. He is the hero as a poet, the bold planner who goes to the battle prepared and yet is forgetful of himself, concentrating on the execution of the work on hand from planes that do not belong to ordinary human consciousness.

Valmiki is not telling a mere story, though that appears to be the surface intention.

Actually, he is taking the civilisations of the past in their entirety to study the step reached so far by mankind struggling towards perfection. The future possibilities are projected by placing before us ideal figures, at the same time warning us from falling a prey to the preyas of our own making.

One who has chosen the life of the spirit must not give way to self-satisfaction and temptation. Precisely the tragedy that befell Ravana, for who is there who has achieved more than the King of Lanka?

Even Hanuman who comes to Ravana’s court with terrible anger at the Rakshasa Lord for having caused Sita’s unhappiness, even he the buddhimatam varistha is for a moment struck dumb at Ravana’s personality. (And we must remember that by this time Ravana has begun to slide down, thus affecting the inner glow of his achievements as a devotee, a tapasvln and battle-warrior):

“What splendour of form! What poise of courage!

~ Sundara Kanda, Sarga 49, Slokas 17-8, Translated by Iyengar, The Epic Beautiful, pp. 352-3

What puissance! What effulgence!

Beyonding all limits, what perfections

hem this proud Rakshasa King!

But for his outrageous unrighteousness,

this mighty Rakshasa King

Could lord it over the world of the gods,

aye, over Indra himself.”1

Valmiki’s Ravana is cast not only in superhuman proportions. He is, in his own way, noble. Valmiki alone could achieve this.

Sri Aurobindo considered Valmiki’s Ravana a masterpiece in characterisation. He felt that though Madhusudan Dutt was able to make Ravana a major hero in Meghnad Vadh, “even then his Ravana is insignificant as compared to the tremendous personality in Valmiki’s Ramayana”. (Talks with Sri Aurobindo, 1966, edited by Nirodbaran, p. 153.)

Valmiki’s characters come to us with immense reserves of symbolism and even seemingly identical cities are described with subtle differences in emphasis, making it possible to study them as symbol worlds.

When Dasaratha’s Ayodhya is described, we see a prosperous city. But Valmiki projects the people and not material grandeur, though the latter is not absent. The sargas, ‘Ayodhya Varnana’, ‘Raja Varnana’ and ‘Amatya Varnana’ give us an idea of perfect citizenship, mutual goodwill and the absence of greed, lust, pride, hate and jealousy. The men and women are young and healthy, well-clothed and well-ornamented. An impregnable city of heroes, and how noble!

Nor only was she grandiosely built,

~ Bala Kanda, Sarga 5, Slokas 20-23, Translated by Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 5, pp. 8-9

A city without earthly peer, — her sons

Were noble, warriors whose arrows scorned to pierce

The isolated man from friends cut off

Or guided by a sound to smite the alarmed

And crouching fugitive; but with sharp steel

Sought out the lion in his den or grappling

Unarmed they murdered with their mighty hands

The tiger roaring in the trackless woods

Or the mad tusked boar. Even such strong arms

Of heroes kept that city and in her midst

Regnant king Dussaruth the nations ruled.

Almost an identical city, prosperous and peopled with heroes is Lanka. But how different!

Valmiki lavishes all the colours in his palette to describe the material magnificence of Ravana’s palace and capital. High living, revelries: but there is no mention of compassion, pity or rectitude with reference to Lanka’s citizens. Everywhere a spread of vital energy:

And moonrise meant the eclipse of the night,

~ Sundara Kanda, Sarga 5, Sloka 8, Translated by Iyengar, The Epic Beautiful, p. 102.

the assault of the blackness

of the heavy meat-gorging Rakshasas

and their riot of revelry:

the scuttling of distrust between lovers

and their immersion in lust:

all this ensued from the efflorescence

of the splendour of moonlight.”2

Man can rise. Unless he is eternally vigilant, he will fall.

To show this, Valmiki presents the contrastive cities and their citizens. In fact, every single line of Valmiki is structured to tell us: “Look here upon this picture and on this,/The counterfeit presentment of two brothers”! (William Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act III, Scene iv, 11. 53-4)[1]

Watch:

Sri Aurobindo on the Significance of Ramayana

Interpreting the Adi Kavya in these terms, Sri Aurobindo says:

On one side is portrayed an ideal manhood, a divine beauty of virtue and ethical order, a civilization founded on the Dharma and realising an exaltation of the moral ideal which is presented with a singularly strong appeal of aesthetic grace and harmony and sweetness; on the other are wild and anarchic and almost amorphous forces of superhuman egoism and self-will and exultant violence, and the two ideas and powers of mental nature living and embodied are brought into conflict and led to a decisive issue of the victory of the divine man over the Rakshasa.

All shade and complexity are omitted which would diminish the single purity of the idea, the representative force in the outline of the figures, the significance of the temperamental colour and only so much admitted as is sufficient to humanise the appeal and the significance.

~ CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 350

It is because Valmiki has succeeded eminently in presenting the two pictures that his appeal has been heard through the centuries in India.

Indian civilisation, despite rude knocks and bufferings, has successfully held on to the ideal of the divine forces though it might have meant suffering and exile; and consistently rejected by and large the blandishments of material success. It is Rama who gives up his kingdom that is called a dheera, a hero, a strong man; and our heroine is Sita who rejects the offer of being made the queen of magnificent Lanka.[2]

Prof. K. R. Srinivasa Iyengar following the path hewed by Sri Aurobindo, explicates the Adi Kavi’s intention as found in the Asoka Vana scene where Ravana meets Sita:

And when the Lord of all this suicidal load of Preyas chooses to confront Sita, like Darkness daring to invade the Sun, like Death facing Savitri in Sri Aurobindo’s epic, the predictable happens. During the fateful confrontation, it is Preyas against the Sreyas that is Sita, for sufferance is Divine. Who is whose prisoner in Lanka? Sita is not Ravana’s prisoner, except in appearance; Ravana is the real prisoner, self-imprisoned by his poisoned appetites. . . The ego-inflated Rakshasa is a darkness that cannot stand the flame of Sita’s Sreyas, her fiery immaculateness and her reserves of primordial Shakti.”[5]

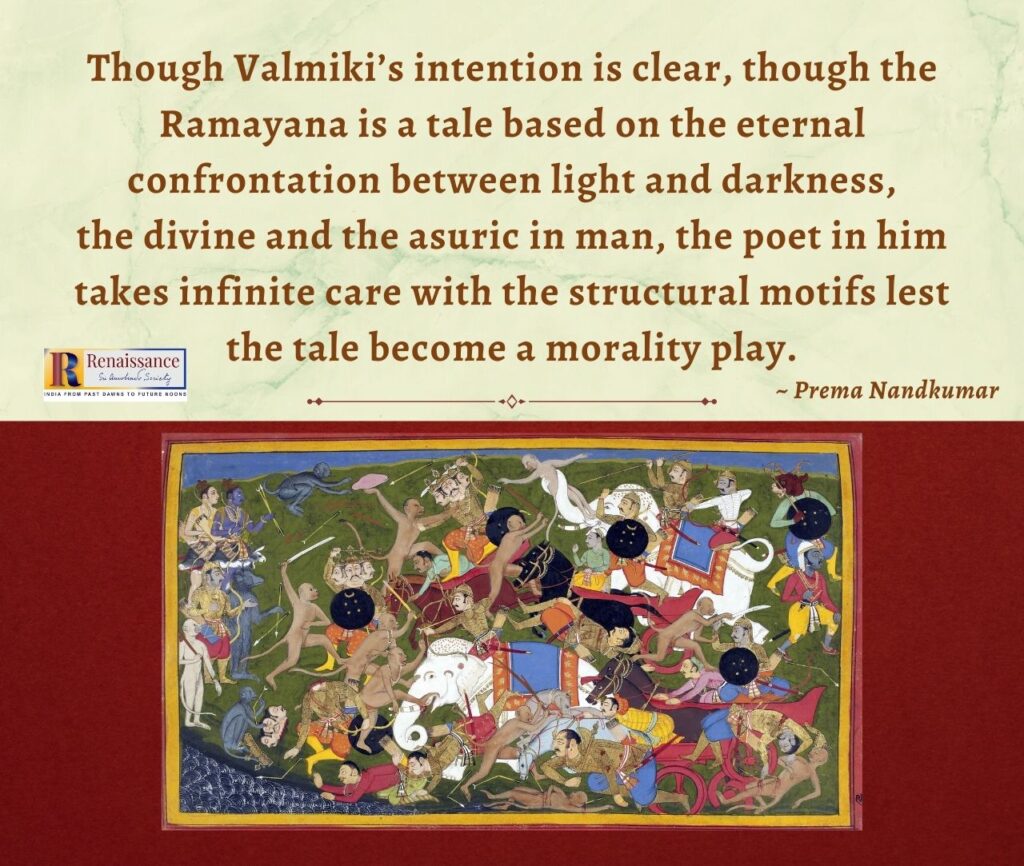

~ The Epic Beautiful

Though Valmiki’s intention is clear, though the Ramayana is a tale based on the eternal confrontation between light and darkness, the divine and the asuric in man, the poet in him takes infinite care with the structural motifs lest the tale become a morality play.

* * *

The Ramayana is a kavya where aesthesis is the major force. The poet’s aesthetic sensibilities which result in kavya saundarya are not the same as algebraic equations. Therefore at the very temple of nobility, veiled malignity builds her shameful shrine of petty jealousy and suicidal tale-bearing. Manthara and Kaikeyi are also part of Ayodhya.

In the same way, Lanka has its pockets of sanity as well. Trijatha in the Asoka Vana, Prahastha softening Ravana’s words when acting as an interpreter in the Court, the wives of Ravana comforting Sita by their compassionate looks and Vibhishana are also part of Lanka. In Sri Aurobindo’s words, such variations as also the killing of Vali are admitted “to humanise the appeal and the significance” of the message enshrined in the epic.

Notes

[1] Also see: “And Hinduism admits relative standards, a wisdom too hard for the European intelligence. Non-injuring is the very highest of its laws, ahimsa paramo dharmah; still it does not lay it down as a physical rule for the warrior, but insistently demands from him mercy, chivalry, respect for the non-belligerent, the weak, the unarmed, the vanquished, the prisoner, the wounded, the fugitive and so escapes the unpracticality of a too absolutist rule for all life.” (CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 149)

[2]“The idealism of characters like Rama and Sita is no pale and vapid unreality; they are vivid with the truth of the ideal life, of the greatness that man may be and does become when he gives his soul a chance. . .” (CWSA, Vol. 20, p. 353)

Continued in PART 4

READ: PART 1, PART 2

~ Design: Beloo Mehra