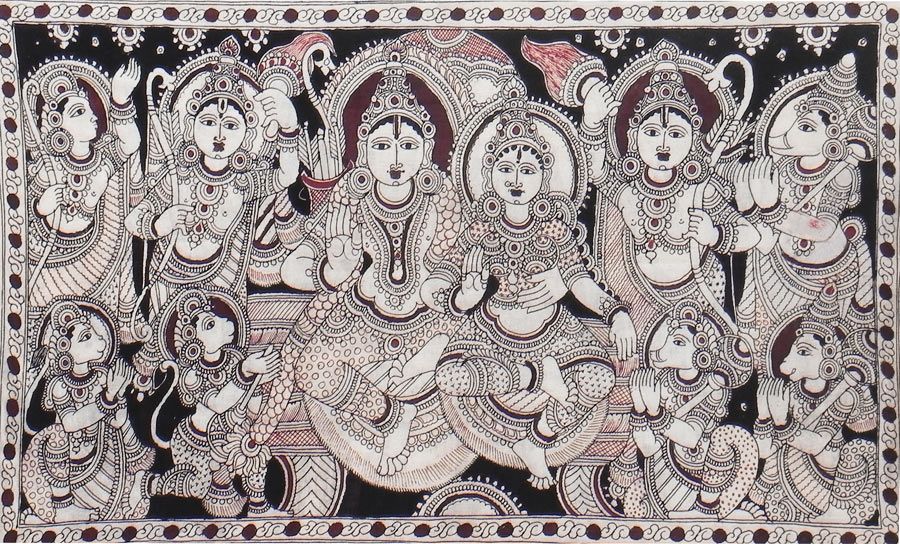

Editor’s note: With the festivals of Navaratri, Durga Puja and Vijayadashmi or Dussehra just behind us, for our Book of the Month offering in this issue, we feature an excerpt from the story of Rāmayana. It is about that episode which has often raised several questions and also some skepticism in the minds of many people — in India and elsewhere. Even those for whom Sri Rāma is an Avatāra of Sri Vishnu, the God Incarnate Himself, sometimes have difficulty comprehending the truth behind this specific episode.

The following excerpt is taken from a monograph edited by Shri Kireet Joshi and written by G. C. Nayak, titled “Selected Episodes from Raghuvamśam of Kālidāsa” (2010). Published by Shubhra Ketu Foundation and The Mother’s Institute of Research, this monograph is part of a series on Value-oriented Education centered on three values : Illumination, Heroism and Harmony. The research, preparation and publication of the monographs that form part of this series are the result of the work and cooperation of several research teams of the Sri Aurobindo International Institute of Educational Research (SAIIER) at Auroville.

The full monograph may be downloaded from HERE or may be purchased from HERE.

The most pathetic and unfortunate episode in the Raghuvamśam occurs where there is a description of Rāma hearing with great concern that the people of Ayodhyā were all praise for him except for the fact that he had accepted Queen Sītā, although she had lived in the palace of the Rāksasa Rāvana for some time. For the people of Ayodhyā, this was an unpardonable sin on the part of Rāma. Naturally, on hearing this slanderous report, —

“The heart of Vaidehi’s consort (Rāma), was as if smitten by that slanderous report, imputing foul disgrace to his wife and therefore unbearable, and broke down like heated iron when beaten with a sledge-hammer.” (Canto XIV. 33)

Although initially Rāma had to face a dilemma, unable to decide what to do, finally he resolved to banish Sītā, though he was sure of his wife’s innocence, as he was convinced that the slander could not be wiped off by any other means, and the glory of the solar race had to be valued more than one’s own body and object of sense. It was Lakṣmaṇa who obediently carried out Rāma’s orders, and started on his mission to leave Sītā near Vālmīki’s hermitage.

One thing that seems to many quite inexplicable, however, is as to why this final decision of Rāma was kept hidden from his faithful and beloved wife, Sītā, and why Lakṣmaṇa was asked to leave his respected sister-in-law near Vāmīki’s hermitage under the pretext of an excursion to see the penance-groves for which Sītā had expressed her longing before her husband. Was it necessary to adopt a course of camouflage in case of a faithful wife like Sītā?

But, then why was this course adopted by Rāma, the ideal husband and also an ideal king? On the other hand, does it not manifest extreme restraint on the part of Rāma? Does it not indicate the exemplary modesty of the husband in restraining himself from communicating to his beloved wife, since it was bound to be unbearable to speak something that was bitterest in his entire life? This can perhaps best be understood by one who has loved most deeply and yet required to do in regard to the object of love something most regrettable but unavoidable on account of the demands of public responsibility that one is required to discharge.

Rāma certainly wanted to prove himself before his subjects to be an ideal king who was not insensitive to calumny; perhaps, he wanted to set a typical model for all his subjects to follow, who would no longer dare to ignore the ideal conduct meant for them in their daily life too. When Lakṣmaṇa informed him about the successful execution of the duty assigned to him for banishing Sītā in the forest, the poet writes about the natural reaction of Rāma to this most unbearable news for him as follows:

“Suddenly Rāma shed profuse tears, as the moon in Pausa (winter season) showers down dew; for on account of the scandal he had cast his beloved Sītā from his home, but not from his mind.” (Canto XIV. 84)

This speaks greatly of Rāma’s deep feelings of tenderness towards his beloved wife and of the profusion of tears that he shed and also of the fact that Sītā was still so very dear to his heart, although cast away from home on account of the scandal in her name.

Sītā was in dire distress after the news of her banishment was suddenly communicated to her in the forest by Laksmana himself; let us see what she says to Laksmana at that point:

“Request the mothers-in-law, greeting them from me in due order: — ‘Pray in your hearts for your son’s progeny that I bear in my womb.’ Next, to the King convey this message from me: does it beseem thy noble race, that thou forsakest me now, at breath of scandal, although my purity was proved in fire in thy very presence?” (Canto XIV. 60-61)

I don’t think that there could be an adequately satisfactory reply to this question raised by Sītā expressed in her dire distress. Finally, of course, she was reconciled to her fate, not because she was a weakling, but again because of her deep love for Rāma, for she said in the next moment:

“Or rather it was no willing act of thine, towards me, since thou art so benevolent in thy disposition. . .” (Canto XIV. 62)

This speaks of her illumined mind in the face of adversity. And then —

“I would have no longer borne this accursed life, all profitless to me through endless separation from thee, had not thy seed, that I bear in my womb, and that must be preserved, proved an obstacle.” (Canto XIV. 65)

She decides then and there to take recourse to penance (tapas) after giving birth to the progeny of Rāma, so that in the next life, she may have Rāma again for her husband but will never be separated from him. What depth of love indeed!

Now let us see what sage Vālmīki has to say about Sītā’s banishment by Rāma in Raghuvamśam, after his meeting with Sitā near his hermitage. Kālidāsa as a matter of fact displays his own deep feelings in this regard, it seems, through Vālmīki who is made to express the following:

“By holy intuition I know that thou art abandoned by thy husband who was agitated by a false scandal: grieve not then, 0 Princess of Videha; thou hast come to thy father’s home in a different country. I acknowledge Rāmā’s greatness in view of the fact that he has uprooted Rāvana who was a thorn to the three worlds, he has also been always true to his vow, and his character is free from any blemish and yet I am sorrowful for his cruel dealings with you without any reason whatsoever.” (Canto XIV. 72-73)

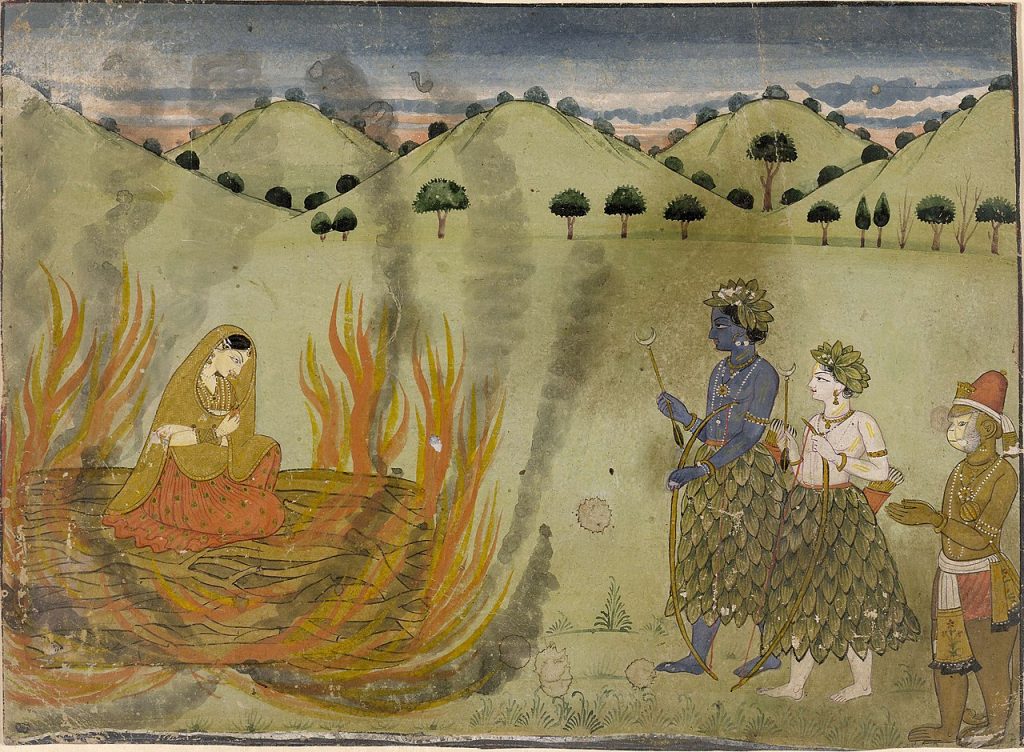

Sītā rather comes out with greater glory in this second ordeal of her banishment much more than when she went through her first fire-ordeal in the presence of Rāma in Lankā. Rāma’s nobility and greatness in remaining faithful to his beloved wife till the end in spite of all this cannot be undermined or under-estimated in any way, for he never accepted another woman as his bride in the absence of Sītā and kept an effigy of Sītā on his side for fulfilling the requirements of sacrificial performances. (XIV.87). Rāma was certainly a great king and a faithful husband, too, but in my opinion, the balance would be slightly tilted in favour of Sītā who is glorious like no one else in the Raghuvamśam.

But at the same time Rāma was both an ideal king and also a loving husband. It is true that he was a loving and protective husband for his wife, Sītā, but unfortunately he had to face a dilemma when he heard of the scandalous report about his faithful wife, and did not know what to do. Finally, he decided in favour of banishing his pregnant and faithful wife to the forest. Calumny was the only ground of Sītā’s banishment.

“Behold, how dark a blot my act has brought on all the Sun-descended race, so flawless in its virtue — stock of saintly Kings — as a cloud-bearing breeze stains a mirror. I cannot bear this slander, the first of its kind, spreading wide among my folk, like a drop of oil on waves of water, even as a mighty elephant hates the post to which he is tied. . .

“I know that she is innocent, and yet public opinion, I hold, prevails: Earth’s shadow cast across the spotless Moon is held by vulgar minds to be a stain on her.” (Canto XIV. 37-38, 40)

Rāma went through a really difficult ordeal in this case, and his greatness both as a faithful husband and as an ideal king remained intact in so far as he decided not to take another woman as his spouse in place of Sītā and also kept an effigy of Sītā by his side, as already referred to, while performing sacrifice, thus displaying his unflinching devotion to his wife of spotless character.

Sītā, it is to be noted, took it as a matter of great consolation for herself and somehow bore the grief of unbearable separation from her beloved husband, on learning about this from different sources at the hermitage of Vālmīki (Canto XIV. 87). However, all the same, the entire episode shows Rāma as king and as husband torn between two most difficult alternatives. And this existential problem for Rāma, was indeed a hard knot to cut.

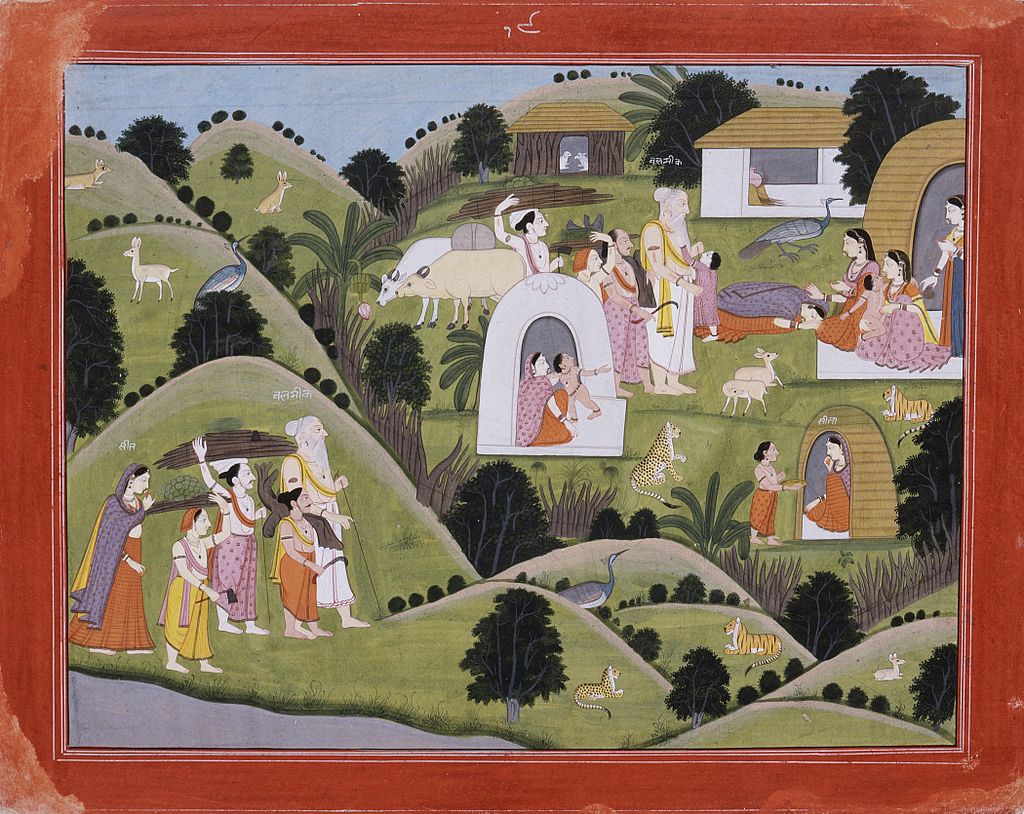

After Sītā gave birth to her two sons in the hermitage, Kuśa and Lava by name, her sons got adequate training in the hermitage under the guidance of the sage Vālmīki himself, and became well-versed and well-trained in singing the Rāmāyana composed by Vālmīki himself. They are also said to have given their performance before Lord Rāmā and his brothers. Rāma, being very much impressed by their singing and on learning about Vālmīki being both the composer of Rāmayāna and the music teacher of Kuśa and Lava both, went to the sage Vālmīki along with his brothers. Here Rāma was asked by Vālmīki himself to accept Sītā, after introducing his sons to him. But Rāma had the following to say in reply, and this is most unfortunate, for again, here, the public opinion holds sway in his mind. Rāma says:

“Sire, this your daughter (Sītā) has been purified in fire in our very presence, but because of the wickedness of the Rāksasa, the subjects here, did not put their faith in it.” (Canto XV. 72)

Again, the demand was made on Sītā by Rāma himself on behalf of the subjects as follows:-

“Let her convince them of her chastity, then I will accept her along with her sons, by your command.” (Canto XV. 73)

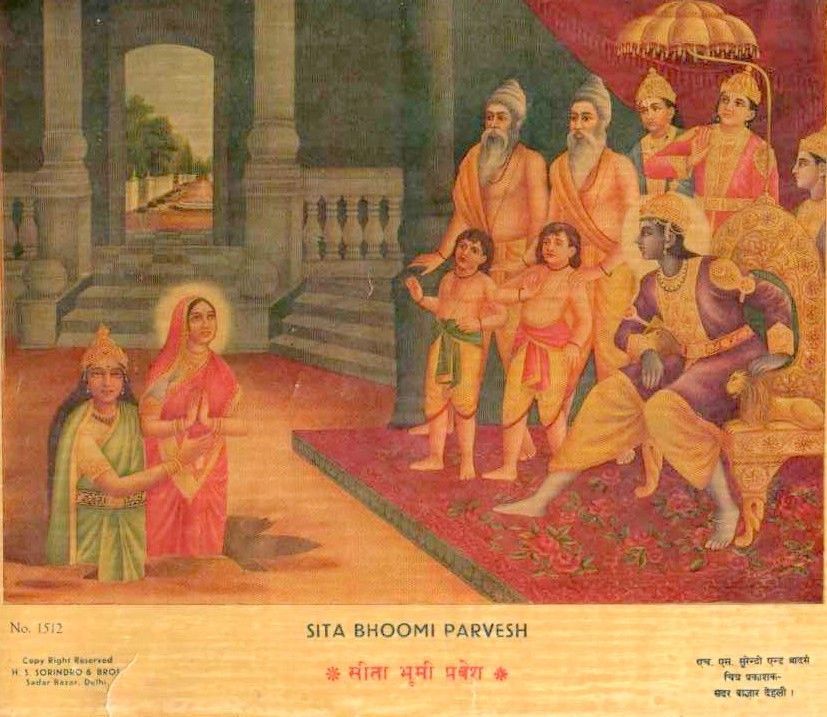

This was indeed too much of a demand for Sītā. However, when the next day, Rāma arranged a meeting of his subjects and called Vālmīki to be present there, the sage ordered Sītā as follows:

“Dear child, let the doubt be removed from the mind of the people, concerning your conduct, in the presence of your husband.” (Canto XV.79)

And here was the climax reached by Sītā in her life already replete with ordeal after ordeal. Sītā had no other alternative now but to give up her life voluntarily after giving her last minute declaration as follows:

“If there is no violation of duty from my side towards my husband whether in speech, thought or action, O divine Earth, the supporter of the universe, please conceal me in your bosom.” (Canto XV.81)

Sītā, to my mind, represents the ultimate victory of a woman of rare honour and dignity. She was well aware of the depth of Rāma’s love for her, and it was really a strong protest of a highly dignified woman.

It is precisely because Sītā was “pure and chaste” beyond an iota of doubt and also because at the same time she was not a weakling or docile as she is made out to be in certain uninformed quarters, she invited her end in this way, without speaking a word to anyone, not even to her beloved Rāma, so that the world at large may perchance learn a fitting lesson from this regarding the excesses done to her by the willful public which had been so very unjust towards her. So, in my humble opinion, there was nothing strange, nothing unclear, about her final response, when she was not left with any other alternative.

Devadhar has rightly pointed out in this context that “Kālidāsa’s account of Sītā’s disappearance tallies with that of Vālmīki’s Rāmāyana, Uttarakānda”. If Rāma was so very disturbed about his and the solar dynasty’s honour being at stake, because of the scandalous reports from the public, it is no wonder that for an honourable lady of the stature of Sītā, it should be intolerable to undergo humiliating situation one after the other, finally ending with a public demand for a second fire-ordeal in front of the denizens of Ayodhyā before her readmission into the royal household along with her children.

What an irony of fate, indeed, that the people felt ashamed at her departure, though they were the cause of her ordeal.

“The people, with-drawing their gaze from the path of her sight, stood with their face downwards, inclined like rice plants with the burden of fruits.” (Canto XV. 78)

Neither Sītā nor Rāma should have tolerated such vagaries of the public mind which was already inclined to blame Sītā in spite of her obviously spotless character. Nothing less than a second fire-ordeal could have satisfied the public that was perhaps curious to see the earlier ordeal to be enacted once again before them.

I am reminded here of the following observations of a famous existentialist thinker expressed in another context which seem to be somewhat relevant here in the context of the citizenry of Ayodhya vis-à-vis the great Sītā and Rāma towards whom it was so very intolerant beyond any reasonable explanation. “It is a fundamental truth of human nature”, says Kierkeggard, “that man is incapable of remaining permanently on the heights, of continuing to admire anything. Human nature needs variety. Even in the most enthusiastic ages people have always liked to joke enviously about their superiors. That is perfectly in order and is entirely justifiable so long as after having laughed at the great they can once more look upon them with admiration; otherwise the game is not worth the candle”.

So strange, and yet so true!

~ Excerpted from “Selected Episodes from Kalidasa’s Raghuvamśam of Kālidāsa”, 2010, pp. 83-91

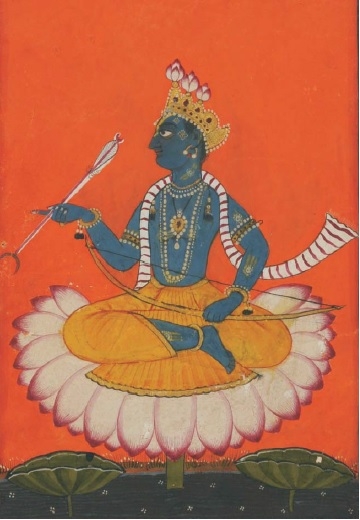

~ Cover painting: Rama’s court, Chamba style painting, 1775-1800, credit: LACMA, source: Wiki commons

For more in ‘Book of the Month’ series, click HERE.